I was in the midst of talking to two friends and fellow competitors — we were participating in a golf tournament in Palm Springs in March — when we heard a voice behind us.

“We don’t want to hear about your period.”

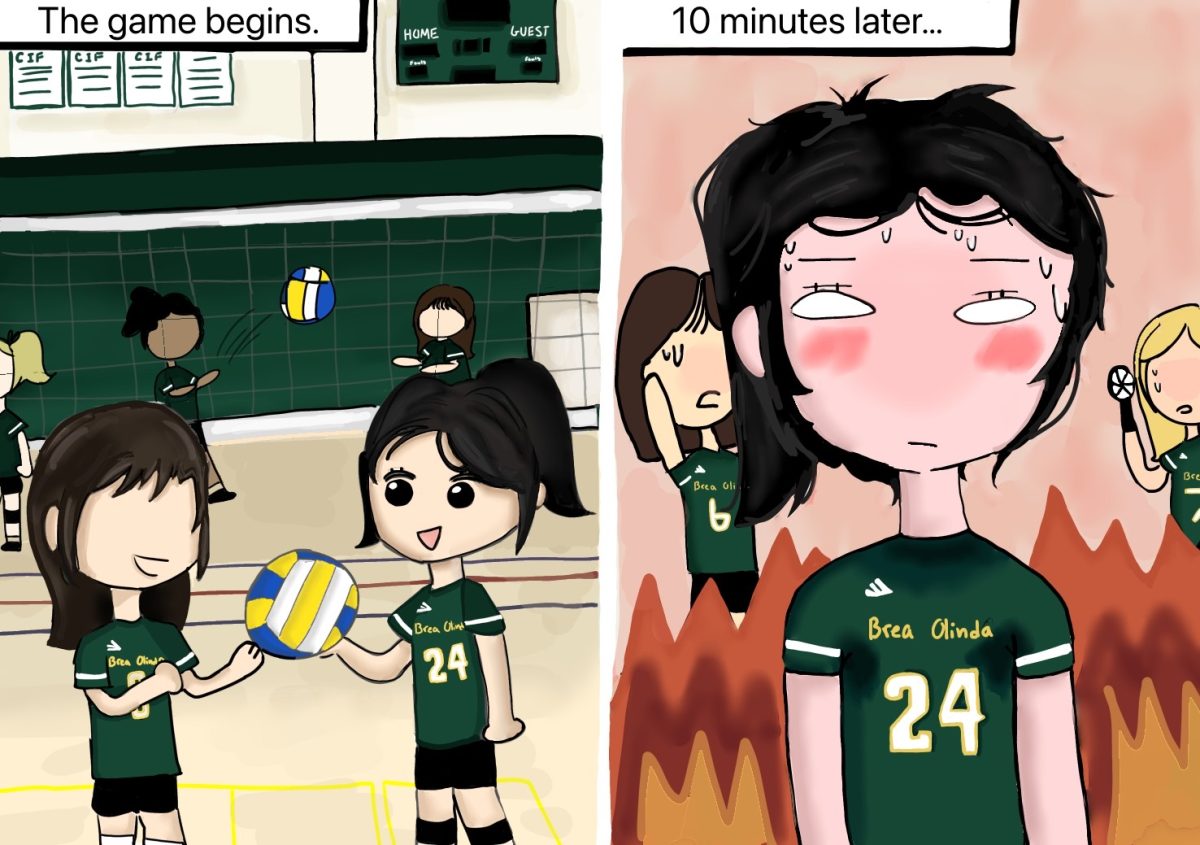

We’d been warming up and chatting about the challenge of being on our periods while playing in tournaments and competing on a course that lacked suitable facilities for its female competitors. (There were only a few porta potties on the entire 18-hole course.)

The speaker was a middle-aged man, a spectator at the event.

Taken aback, we wondered where he found the audacity to speak about our bodies.

But this wasn’t my first time experiencing extreme discomfort at golf events.

Many of the more popular tournament venues — like El Prado in Chino and Hesperia Country Club — lack the facilities to accommodate the 80-plus female athletes competing over five- to seven-hour rounds. Bathroom access is limited, often just two or three dirty portable sheds scattered throughout the courses.

For female competitors on their menstrual periods, this means struggling, both physically and mentally, for hours, unable to take care of the most basic hygiene.

A few seasons ago, at a national-level tournament in Palm Springs, I was forced to tell a male rules official that I was on my period so he could drive me by golf cart to a clubhouse bathroom because on the course, there were zero bathrooms with running water.

I never thought something so normal — something 1.8 billion women experience every single month — could also be a source of shame, of embarrassment.

But the lack of access to bathroom facilities with running water and pad and tampon dispensers, and the occasional ignorance of strangers, are not exclusive to the world of golf.

The lack of resources and knowledge is testament to a state-wide failure to sufficiently educate its population about menstrual health.

California schools, including BOHS, do not provide enough formal education on menstrual health, resulting in a severely — and dangerously — uninformed population.

Currently, the only opportunities BOHS students have to reliably learn about female bodies outside of the home and their doctor’s offices are via the online APEX health course during summer school, or in one of only two periods of Health offered on campus.

Neither of these options adequately address menstrual health.

For instance, Apex, which most of BOHS’s student body takes for their health graduation requirement, barely covers menstrual health, with just a single subsection in its “Reproductive Systems” unit. Within seven units of four to five subsections each, in a course that takes dozens of hours to complete, not a single lesson is dedicated to the topic.

Angela Sohn (‘26), who took the Apex health course in 2023, acknowledged that the curriculum “could have done a better job of educating students on different kinds of period products and solutions to period pain.”

There is no information about the dangers of the exposure to toxic chemicals from commonly used feminine hygiene brands; no information about uterine health; and no information about the availability, use, and even dangers of tampons.

But Apex Learning is not entirely at fault for including so little education about menstrual health in its curriculum — they’re simply following the state of California’s framework for health education.

The official California Health Education Content Standards — a 71-page document — does not have any independent sections or subsections on menstrual health. The only section that potentially allows for the teaching of the topic is under the “Growth, Development, and Sexual Health” segment, under Standard 1, 1.1.G, which reads: “Describe physical, social, and emotional changes associated with being a young adult.”

That’s it.

There aren’t even lessons on menstrual health under the “Personal and Community Health,” “Health-Enhancing Behaviors,” and “Health Promotion” categories. (Units on abstinence, sexual diseases, and drug and alcohol abuse make up the majority of the health content standards for California public schools).

On the BOHS campus, menstrual health is similarly overlooked.

Sophie Ho (‘25), who took the on-campus health class her freshman year, recalled that the class “didn’t cover [the period] too much,” just a short lecture on toxic shock syndrome and the use of tampons and pads.

Like Apex, BOHS’s health program is just following the lengthy list of state standards it is required to cover in the one-semester class. Ultimately, however, this lack of formal education makes it difficult for young women to fully understand their bodies.

Not all women, like Ho, have access to the internet or a doctor, leaving far too many young people without the means to learn about menstrual health. Thus, it is essential that young women are are being educated in their mandatory high school health classes, and not from misinformed peers or unreliable internet searches. And it’s not just girls who benefit: boys learning about women’s bodies helps normalize menstruation, develops empathy, and creates a more “inclusive and equal society.”

The lack of education leads to societal pressure to make women feel the need to hide their bodily functions; a stigma about discussing the menstrual cycle; and the failure to provide forums for sharing life-saving information (like the presence of lead and arsenic in “widely available tampons”).

If California requires its high school students to graduate with “knowledge, skills, and attitudes in eight overarching standards,” including “essential health concepts,” “accessing valid health information,” and “practicing health-enhancing behaviors,” it’s vital that mandatory health curricula across the state expand the amount of time and lessons dedicated to women’s menstrual health. The state can’t let under-education perpetuate social stigma, lack of resources, and health hazards that women are facing now.

The health of its women depends on it.