In seventh grade, I discovered my favorite book, Interior Chinatown by Charles Yu, in a serendipitous way: On TikTok, my favorite YouTuber read an excerpt from Yu’s novel about karaoke and Taiwanese immigrants and John Denver’s twangy hit, “Take Me Home, Country Roads.”

I am not Taiwanese, nor am I particularly fascinated with “Take Me Home, Country Roads,” but I had never read something that so deeply resonated with me. It took me a long time to figure out why this book about kung-fu and fake Asian accents made me feel so seen.

But at its core, Yu’s book is about the Asian American experience, something that, despite being Asian American myself, was something (at least then) I did not fully understand. The book was a mirror and I could see myself, and my family, on every page.

However, while I’ve seen myself reflected in the literature I’ve read, and have enjoyed glimpses into the lives of Asian American authors like Yu, Amy Tan, and Chang-Rae Lee, the novels and essays are just that — glimpses — and have not more fully informed me of the Asian American diaspora — its sociopolitics, its diversity, its histories.

On Oct. 8, 2021, Governor Gavin Newsom addressed this educational blindspot by signing into law bill AB-101, which mandates that all California high school graduates in 2030 and beyond are required to take either a stand-alone ethnic studies course; be taught ethnic studies as part of an already existing A-G-approved course (like English or history); or experience a “locally developed ethnic studies course,” like at a college or university. Ethnic studies will, according to Newsom, “enable students to learn their own stories, and those of their classmates.”

But on May 13, despite the progress made to develop high school ethnic studies programs throughout the state and just months before the mandate was scheduled to go into effect, Newsom’s office announced that it is withholding state funding due to “limited available ongoing resources” according to a spokesperson for the state’s Department of Finance.

Despite the pause and the uncertain future of the mandate, schools, including BOHS, should still move forward with ethnic studies curricula, because Newsom was right: An ethnic studies curriculum enables students to learn not only about themselves, but also about their peers, ultimately creating a more just, understanding, and empathetic society.

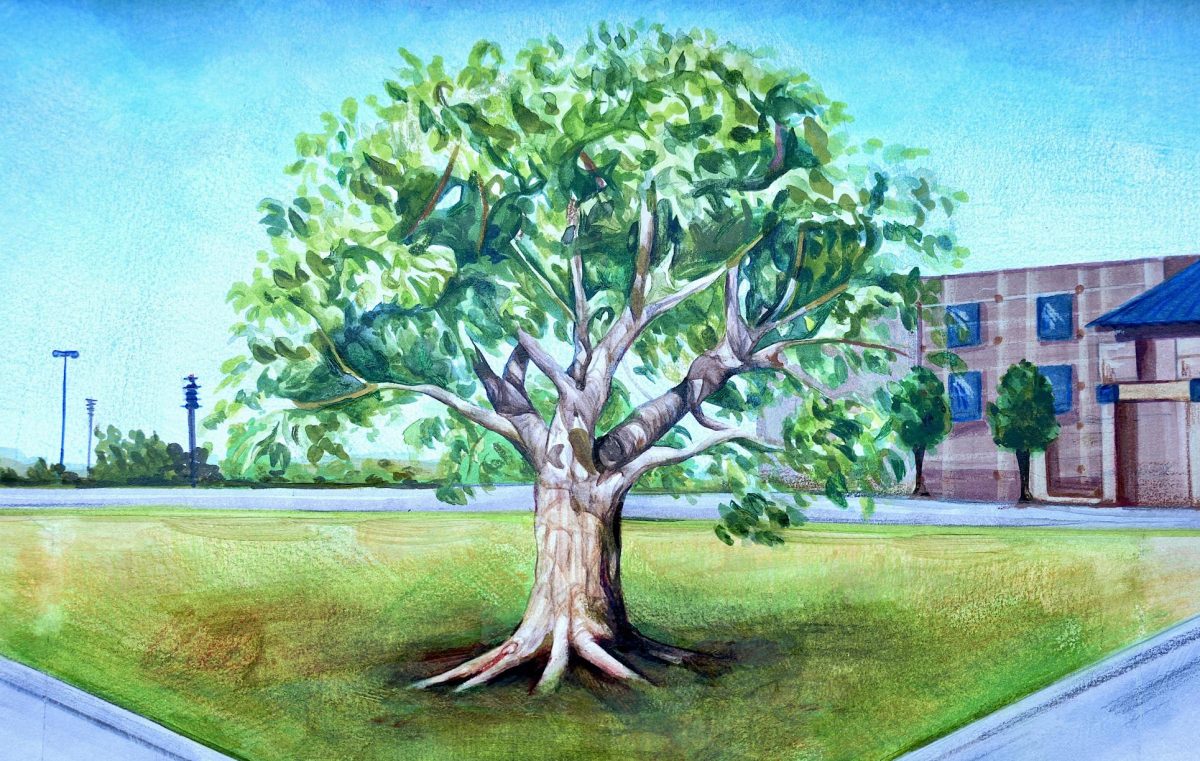

At BOHS, with a student body that is 71% Hispanic, Asian, Black, Pacific Islander, and Indigenous, it is essential that we adopt an ethnic studies education that goes beyond what we read in our history texts and assigned readings in English.

Because ethnic studies is more than the study of U.S. history and novels by Black and Asian authors; it is “an interdisciplinary field of study that encompasses many subject areas including history, literature, economics, sociology, anthropology, and political science. It emerged to both address content considered missing from traditional curriculum and to encourage critical engagement.”

The mandate would expose 5.8 million California students — including BOHS’s population of 1648 — to ethnic studies, but with Newsom reneging on his support of the mandate, schools, including ours, are no longer required to develop an ethnic studies curriculum.

Originally, BOHS was planning on developing one one-semester ethnic studies course, paired with a semester of psychology. Students not enrolled in that pairing would fulfill their ethnic studies requirement piecemeal, via ethnic studies-related lessons woven into pre-existing classes like Literature and Composition I and U.S. History.

That’s still a step in the right direction, but also inadequate given the scope of the state’s ethnic studies framework, which spans things like the roles “African Americans have played in the advancement of science, technology, and other areas in American society”; the “sovereignty of Indigenous lands and sacred sites”; and the positive and negative effects of immigration policies.

Regardless of the mandate’s pause, BOHS should move forward with its integration of ethnic studies into its students’ education, and add more sections of stand-alone ethnic studies classes as elective options. To sufficiently educate our student body about relevant topics regarding race, gender, and ethnicity in American society, it’s vital that we have this choice.

BOHS would join some of its north Orange County neighbors that have already added ethnic studies electives in its course offerings. Fullerton Joint Unified School District’s (FJUSD) Sonora, La Habra, Sunny Hills, Sonora, and Troy high schools, for example, all have ethnic studies electives. Even more ambitious is Anaheim Unified High School District which created its own ethnic studies graduation requirement and offers a diverse array of classes like Asian American Studies, Latin American Music and Dance, and U.S. History Ethnic Studies. Currently, state-wide, about 50% of public high schools already provide students with some ethnic studies courses.

BOHS should join its forward-thinking neighbors and provide its student body with a sufficient education in ethnic studies, learning that involves lessons and units about roles played by race, ethnicity, and culture in an increasingly-diverse American society.

In a time where division between people and communities seems like the norm, providing students with education about the past, present, and future of various races, ethnicities, and other pressing subjects in American culture is a necessary step in the right direction, a step forward towards a more tolerant, cultured, empathetic, and just society.

Adeline Robertson • Aug 23, 2025 at 4:22 pm

I love this! So well written!