When Joey Davis stepped into the role of principal at Brea Olinda High School last year, his immediate priority was not policy change or implementing new programs, but to build relationships, and to learn and grow a culture unique to Wildcat Way.

Upon arriving at BOHS in 2024 — his 36th year in education — Davis noticed a difference between his new site and Valencia and El Dorado high schools, where he served as assistant principal and principal, respectively. At the larger schools — Valencia’s enrollment is 2400, El Dorado’s 2000 — teachers and administrators serve in more specialized roles than their counterparts at BOHS with its smaller staff and student body of 1590 students. Davis realized that to learn the rhythms of his new campus, he needed to build strong, enduring connections with the staff.

“Getting to know the staff,” Davis said, “was the most important thing.”

More than reaching specific educational goals in his first year, Davis aspired to a culture of community and friendship.

One sure-fire way to make connections with others: food. Before winter vacation last year, Davis borrowed from Valencia’s tradition of cooking pancakes for students three times a year and used BOHS’s culinary classroom to cook breakfast burritos with faculty and staff, both to get to know his new colleagues better, and to spark traditions that he hopes will continue long after his tenure.

“Ten years from now, it would be nice to hear that traditions like that are still going on,” Davis said. “Hopefully this year we can build on those connections.”

While concurrently forging trust with a staff who had experienced three principals in the previous seven years, Davis had to adapt to a host of challenges on his new campus.

In the first 10 months of his tenure, BOHS experienced: a Wi-Fi outage that postponed AP testing; a natural gas leak caused by drilling from the new fence construction; and two threats of school violence, one in September and another in November — the latter resulting the cancellation of all classes and on-campus activities.

Davis admitted that his inaugural year wasn’t without its obstacles, but obstacles are expected in education, especially in educational leadership.

“You’re always going to have challenges,” Davis said. “If [the job] were easy, it wouldn’t pay us.”

But 2024-2025 was also marked by progress.

In the spring, the Link Crew program doubled from one section to two to better support incoming freshmen; BOHS met goals for state testing in CAASPP for Language Arts and science; and the school increased the number of students passing AP exams from 82% to 89%, and increased the number of AP exams taken by 62. Additionally, survey data showed that freshmen — the class that typically needs the most support — felt the most connected to the school community.

Davis sees these wins as a sign that BOHS is changing for the better, but he also recognizes that sustaining progress requires building a stronger sense of connection for every grade level, not just the incoming freshmen.

“What I really want to build on is the culture aspect [of BOHS],” Davis said.

One of Davis’s primary goals for this school year is to strengthen BOHS’s culture of connectedness, which he models by being active in campus activities — a “responsibility” he enjoys.

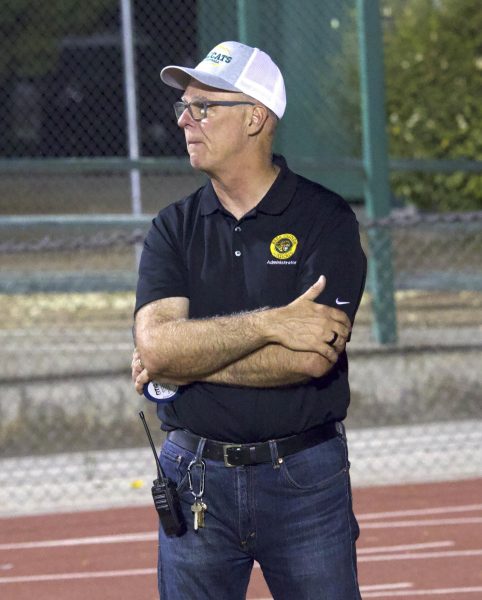

For instance, in nine years as principal at two schools, Davis has only missed three varsity football games. That tradition of being present on the sidelines every Friday night continues at BOHS: At the Wildcat football game Aug. 22, Davis walked the sidelines, chatted with BOUSD staff and students, and cheered on the team (47-0 winners over visiting Sonora High School).

“What’s a bigger event for students and their families than Brea Olinda football games?” Davis asked.

Davis is also a frequent presence at other campus activities: from watching boys’ and girls’ volleyball games, to occupying a seat in the Performing Arts Center (PAC) for drama, dance, and choir shows, to canvassing the quad to interact with students during snack and lunch.

The time commitment is a sacrifice he happily makes. “Sometimes in my personal life I have to set other things aside to make sure I can be there for the school and the students,” Davis said.

Though he can’t personally connect with all 1590 Wildcat students, Davis uses campus events and breaks during the school day to be more than a principal, but also a familiar face and part of the fabric of school culture.

“I don’t get the same opportunities as a classroom teacher, where they get to see [students] 180 hours a year,” Davis said. “I might only get 10 minutes during breaks, so I try to do what I can to be visible.”

Davis’s commitment to improving the school goes beyond being present at campus activities, however. He’s ensured that BOHS classrooms are outfitted with 85-inch TVs; he personally recruits BOHS student representatives to the Superintendent’s Community Advisory Committee; he participated in an e-bike training initiative led by Brea PD, which requires students who ride e-bikes to campus go through safety training to obtain a permit (which about 70 BOUSD students have completed so far, according to Davis); he encouraged faculty to create “classroom agreements” to further community building; and even personally replenished a dwindling paper supply in the main office.

“I can’t expect others to do what I’m not willing to do” Davis said. It’s a motto he imbues into his work ethic, believing that, as the district’s only high school, excellence is required of the school.

“There’s an expectation that [myself and the staff] are doing things really well,” Davis said, noting that while students in other districts may have five to six high schools to choose from, like neighboring Placentia-Yorba Linda Unified School District (PYLUSD) and Fullerton Joint USD, the academic experiences of Brea’s adolescents rest solely on BOHS and its leadership, faculty, and staff.

“I want kids, teachers, office staff, and everyone else to have those same [high] expectations,” Davis said.

As he looks ahead to the next few years, Davis envisions an ingrained culture of trust and tradition at BOHS. Though he knows it won’t be easy, he recognizes that in the pursuit of doing what’s best for kids (“Which is what all schools should be doing,” Davis said.), the community may not be unanimous on what that course may be.

“Over time, we’ll get to know each other and realize that we’re all in [education] for the same reason,” Davis said.

For Davis, that reason — improving students’ social and academic lives — led him to prioritize culture-building, showing up, creating connections, and leaving behind traditions that last on Wildcat Way.

Jacquelyn Nethers • Aug 27, 2025 at 5:47 am

Appreciate all the positive changes at BOHS! Great reporting, Sofia!