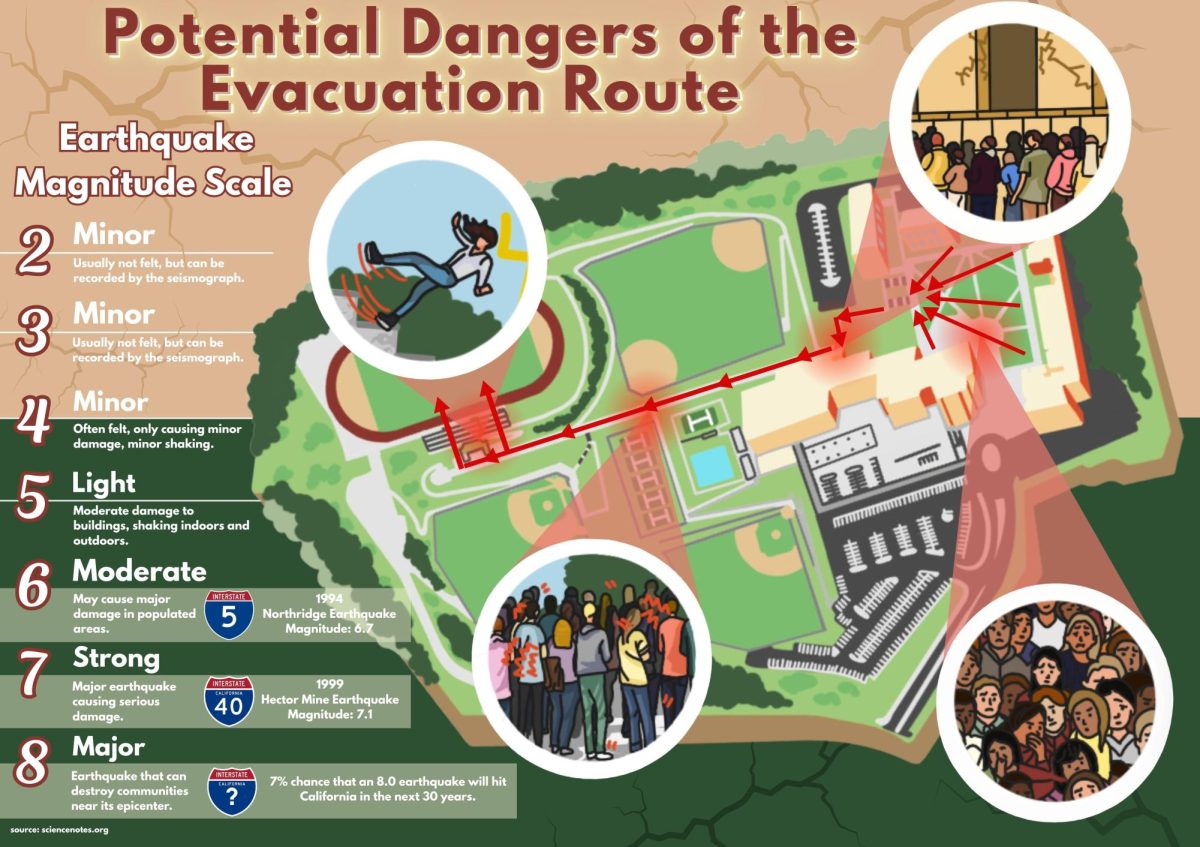

When the Northridge earthquake struck at 4:31 a.m., Jan. 17, 1994, communities from the San Fernando and San Gabriel valleys to the South Bay’s beaches were jolted awake by 10 seconds of violent shaking that resulted in catastrophic loss and destruction. The quake was felt as far away as Phoenix 400 miles to the east, and Ensenada, Mexico, 230 miles south.

While 6.7 magnitude quakes are rare — only two others, the Hector Mine and Ridgecrest quakes, both with magnitudes of 7.1, have occurred in California since 1994 — they are an ever-present possibility. In fact, the Uniform California Earthquake Rupture Forecast warns that the Los Angeles area has a 60% chance of a major earthquake within the next 30 years. Because Brea sits near the Whittier and Puente Hills fault lines, our community is especially vulnerable to seismic events.

The Great ShakeOut, conducted Oct. 16, is the world’s largest earthquake drill, with 58.5 million participants worldwide. Participants practice dropping, covering, and holding on, and workplaces and schools, like those throughout the Brea Olinda Unified School District (BOUSD), rehearse evacuations.

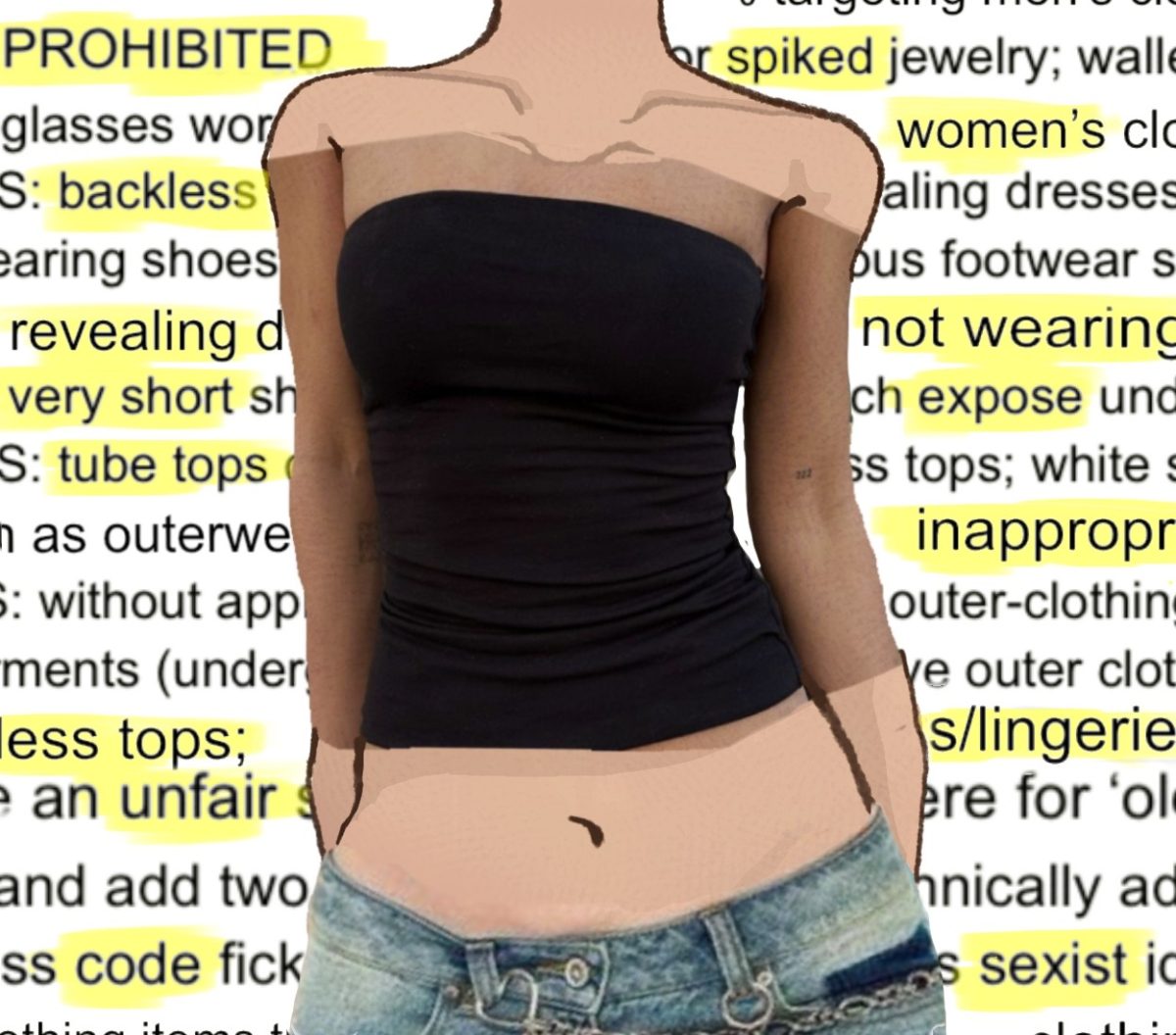

On the day of the drill, at 10:16 a.m., an alert was broadcast over the loudspeaker. Some teachers reacted with appropriate seriousness and required students to seek protection beneath their desks, while other teachers sent their students to the evacuation route without any urgency.

Then, despite the gravity of the drill, students leisurely emerged from classrooms as if they were on the way to lunch, not fleeing the inevitability of collapsing buildings. There were no orderly lines, but rather hallways jammed with slow-moving knots of students and faculty, boredom and irritation propelling feet forward, not the expected urgency of a life-or-death situation.

Some teachers, hoisting orange flags and toting red emergency bags, did their best to guide the mass of students, shouting directions over the din of conversations.

The drill route snaked down crowded stairwells, across the quad, through the dangerous bottleneck between the gym and softball fields, and finally, down the concrete steps of Wildcat Stadium. Students and faculty not assigned to emergency roles were assembled by the hundreds on the field.

The route is dangerous every step of the way, and not just from an earthquake, but from the actual path from classrooms to the field, a path that’s supposedly meant to lead us to safety.

The most obvious danger along the long route (which is a third of a mile from the Wildcat newsroom to the stadium), is the narrow passage beneath the cafeteria area and past the gym, softball fields, and tennis courts. Students, all 1650 of them — shuffle under towering stone columns and beside aging trees lining the sidewalks.

The evacuation route is a death trap, and it’s too easy to imagine what will happen during an actual earthquake: crumbling columns, surges of panic, trampled students.

BOHS must revise its evacuation procedures and route, one that will safely direct students away from falling hazards.

The Wildcat proposes:

- The spacious quad should be a rallying point for classes from the north and west wings.

- The softball fields, just steps away from the New Building and adjacent to the current disaster command center, should be the meeting point for that building.

- The roundabout can be a rallying point for the administrative, athletics, and performing arts buildings, with a wide pathway for escape down Wildcat Way.

- Faculty should better emphasize the importance of the drill, enforce ducking and covering, and direct their students to the safest areas of assembly on campus.

Each of the aforementioned locations eliminates the most dangerous point on the route — the bottleneck at the gym — and ensures that students and teachers can gather quickly until it’s safe to evacuate down Wildcat Way.

Currently, the drill is performative, a box — the “Great ShakeOut” box — to check. Instead, BOHS should revise the evacuation drills, and treat emergencies, including fire and active shooter drills, with gravity and urgency and as more than a chore, an inconvenience.

The BOHS community, from students, to staff, to faculty, needs to implement practices that are consistent, serious, and steady, even when the ground beneath us isn’t.