Drought conditions, hurricane-force winds, and fallen power lines contributed to the deadliest natural disaster in Hawaii’s history: the Maui Wildfires.

The death toll from the Aug. 8 fire reached 115, but state officials worry that the number may increase as the search for over 300 Maui residents still unaccounted for continues. The National Fire Protection Association declared the fire the fifth deadliest wildfire in U.S. history.

The strong winds of Hurricane Dora — rated Category 4 on the hurricane severity spectrum — fanned the flames to unprecedented size, burning 2,170 acres and leveling Maui’s historic town of Lahaina.

Captain Chris Marvin, of the Brea Fire Department, explained to the Wildcat that “a wildfire, by definition, is an uncontrolled fire that burns in the wildland vegetation, often in rural areas, but sometimes burns into urban areas like Lahaina. Once a wildfire starts, it is driven by fuel, topography, [and] terrain.”

Over 16% of Maui County has been in a drought since 2008, and an additional 67% of the island today is “abnormally dry,” according to the U.S. Drought Monitor. The Mauna Loa Observatory examined a 32.3 F increase in temperature — the result of declining rainfall and warmer temperatures.

The drought, extremely dry conditions, and hurricane winds made the island more susceptible to the blaze. Andrea Ramos, AP Environmental Science teacher, explained that “hurricanes like [Dora] lead to greater winds, which cause power lines to break and spark.”

Marvin said, “The intensity of these wind-driven fires is unfathomable. Scientists say the rate of fire spread is one football field every three seconds with winds at these speeds.” The fire captain added, “Think about that.”

The combination of sparks from fallen power lines and high winds allowed the quick spread of flames.

Marvin explained the differences between the Maui fires and the Blue Ridge and Silverado fires that swept through Brea in October 2020. The latter two fires “burned mostly in rural areas, destroying six homes total [with the] highest wind speed being 20 miles per hour,” Marvin said. Comparing the two fires is “really [like] comparing apples to oranges,” Marvin added, because in contrast, the Lahaina fire’s wind spreed was recorded at 81 miles per hour, burned through 2,170 acres and 2,207 structures (86% residential) of urban land.

“As we have seen in this fire,” said Marvin, “there is no stopping mother nature’s fury.”

“When I heard about the fires, I was terrified,” Sydney Eaton, Lahaina resident and sister of BOHS history teacher Brittany Eaton, said. “They were spreading so fast, too fast for some people to evacuate.”

Eaton said of Lahaina: It’s “full of life, energy, and joy,” but after the wildfire, the town looked “apocalyptic.”

Marvin shared that even well-equipped departments “cannot safely fight these fires directly due to their intense heat and forward progression.” In these situations, states that have evacuation notification systems “consistently work hand in hand with police departments to evacuate areas when possible.”

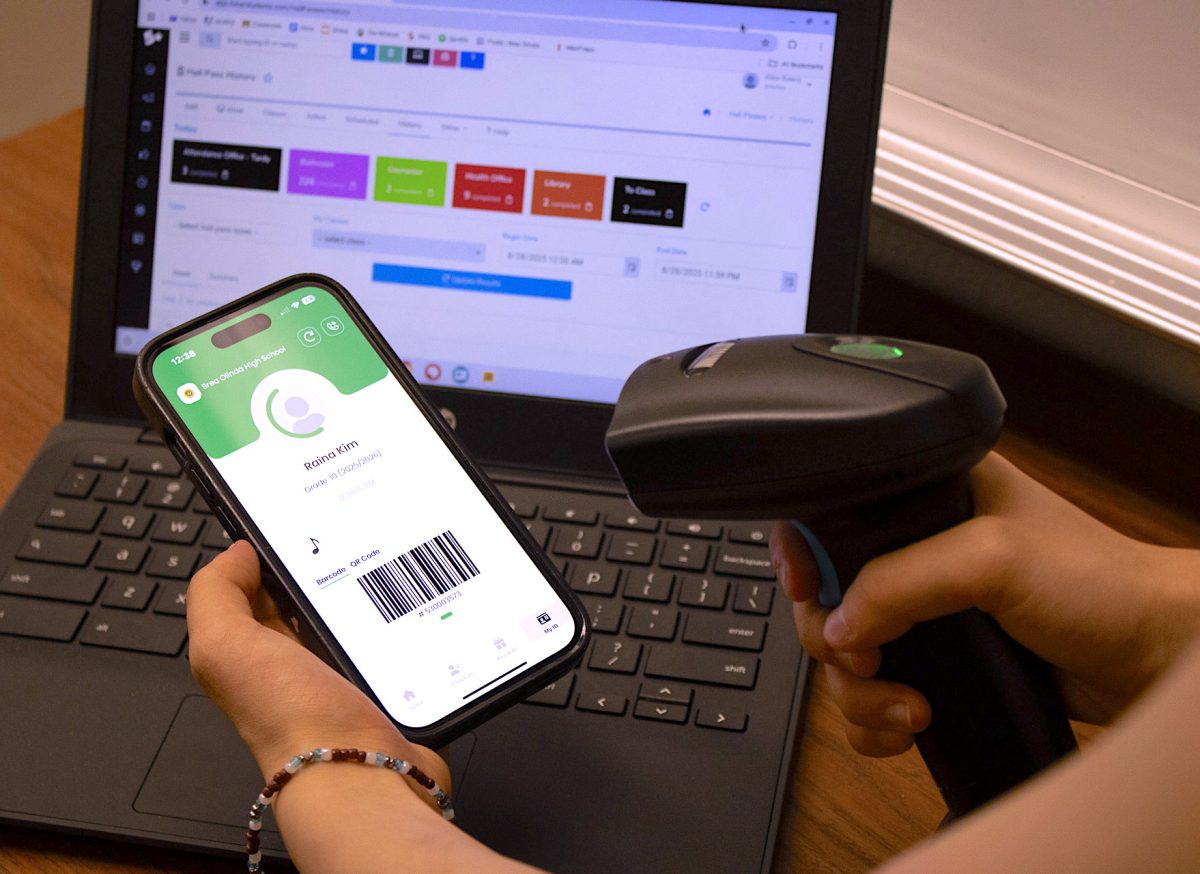

However, Maui’s all-hazard siren system was not working at the time of the fire, despite wildfires being listed by government pages as one of the emergencies that require the proper use of alerts.

To ensure safe evacuation in times of emergency, Hawaii installed 400 sirens in 1946 after a tsunami led to over 160 deaths as result of an earthquake on the Aleutian Islands. The sirens ring at 121 decibels stretched across a 3,400 ft (half-mile) radius, and are intended to alert residents to evacuate promptly. Hawaii’s Department of Defense claims that “Hawaii has the largest single integrated Outdoor Siren Warning System for Public Safety in the world.”

However, the sirens were never activated during the blaze, meaning “the city of Lahaina [had] zero warning that a fire inferno was coming,” Marvin remarked.

When questioned at a press conference on Aug. 16 whether the officials regretted not activating the alarms, Hernan Andaya, chief of the Maui Emergency Management Agency, asserted “I do not.” In the wake of widespread criticism, Andaya resigned “effective immediately” the next day.

While the agency sent mobile emergency alerts to mobile devices, radio stations, and televisions, residents in areas with power outages reported that they did not receive any warnings and were unaware of when to evacuate.

Eaton revealed that due to the lack of cell service and power, the only way people could seek safety was waiting for police to arrive at their door, ordering them to evacuate. Eaton, who was not in Lahaina at the time of the fire, said, “I was terrified [and] laid awake at night, not being able to be in constant communication with anyone, and not knowing if they were okay.”

Eaton finally experienced a sense of relief when her fiancé “found a pocket of service around 3 a.m.” to let her know he and their dog were safe. During that phone call, her fiancé shared the haunting details of the disaster, and words that she will never forget: “Lahaina is gone, it is just all gone.”