Last year, instead of conversation and social interactions, the last few minutes of periods were often spent in silence. Instead of interacting with their classmates and teachers, students resorted to another source of engagement: their phones.

To combat this pervasive phone use, BOHS administration implemented a new cell phone policy, which they presented at grade-level assemblies on Aug. 15.

“Something procedural is what we needed,” Fernando Grimaldo, vice principal, said.

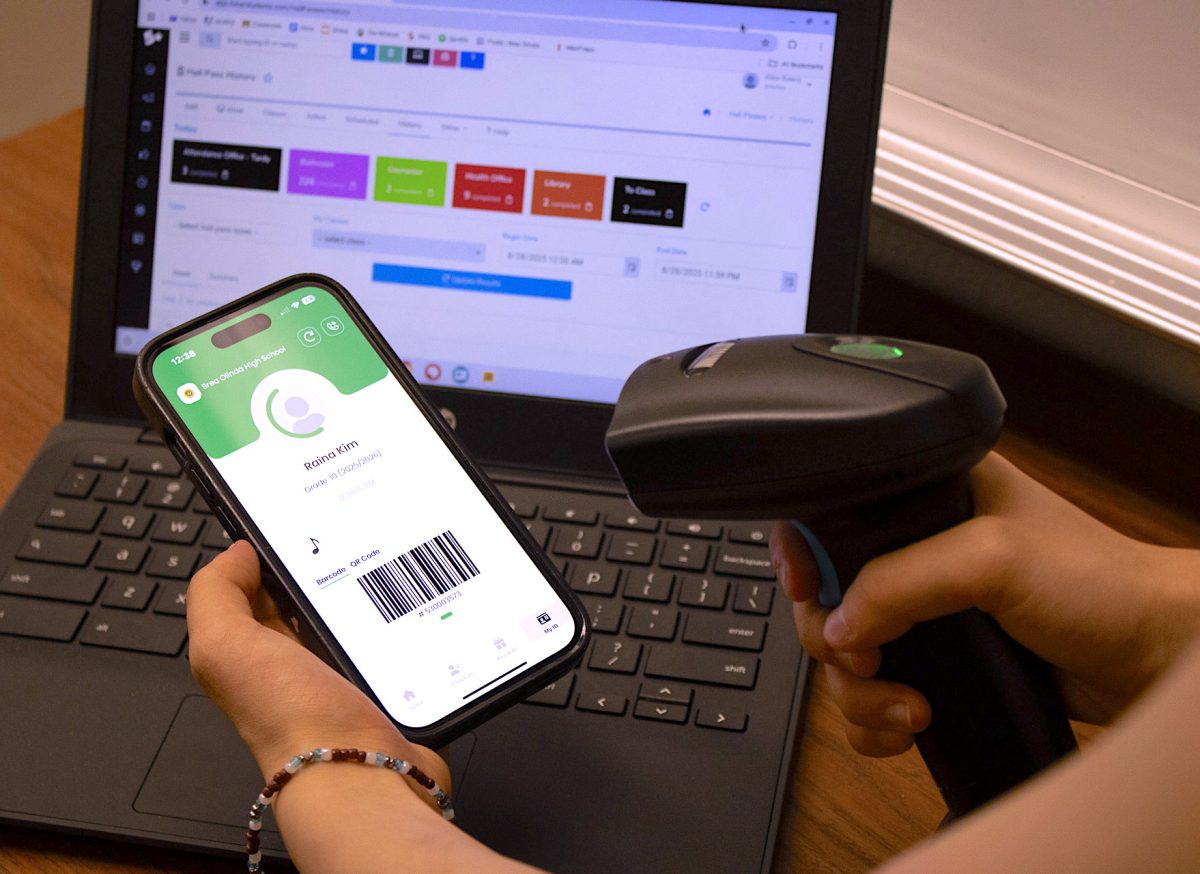

The new policy is a more definitively outlined process, versus the verbal warnings of teachers in the past. If a student is caught using their phone without permission in class, teachers will give up to three verbal warnings. If the student does not comply after the third warning, a campus supervisor is called to the classroom to confiscate the device and take it to the main office. There, school administrators label the phone with the student’s name and secure it in a drawer where it can be retrieved at the end of the school day.

Though teachers have taken preventative measures — such as numbered phone caddies and “phone jails” — to curb cell phone use in the past, this policy introduced the first, “uniform and school-wide [rule] that everybody has been informed about and everybody will adhere to,” Mary Grigoli, chemistry teacher, said.

According to Michelle Garcia, administrative assistant, about 10 phones are confiscated each day.

“We’re not joking around,” Grimaldo said. “We really want our students to be successful, and we feel that a device like [a phone] is going to be distracting to the learning.” Grimaldo further expressed that cell phones — a “disruption in education” — have resulted in students “struggling in the classroom.”

Gil Rotblum, history teacher, has already noticed an improvement in student behavior since the policy’s implementation. “This year’s students are more compliant when I say, ‘put away your phones,’” he said.

Also in support of the ban is Brian Schlueter, history teacher. “We only get less than an hour of class to focus on the things we need to work on, and we just have so much to do, that we really don’t need to get another distraction,” he said. Phones, he added, “take away from productivity and relationships.”

Jill Matyuch, psychology teacher, has also noticed an increase in student engagement. Compared to last year, this year, “students communicate verbally, they get to meet their classmates, and they are more present” in class, she said. “I think enforcement [of the policy] is necessary for healthy intellectual and interpersonal skills.”

Rotblum agreed: “You can see kids are happier when they’re actually engaged and talking with other people. You can read it in their body language, their mood, and the overall environment of the class is just so much better.”

Students are also noticing a difference in classroom behavior since the policy’s implementation. After Siwon Bae, sophomore, finishes classwork, she has noticed that her “friends actually talk to each other,” which “is different from last year when [students] were Snapping and sending messages.” Bae admitted that, last year, she would spend the last few minutes of class on her phone. “[But] I don’t look at Instagram at all [during class] anymore,” Bae said. “It’s disrespectful to teachers.”

Joshua Yun, junior, said that the enforcement of the policy helps him focus in class and “have more self-control.”

However, some students are not fans of the “no tolerance” policy.

Sophie Kim, senior, misses “the convenience of being able to research information on cell phones.” The policy “disrupts my workflow,” Kim said.

“It’s understandable that teachers don’t want their students playing games, but there’s no reason we can’t be checking our grades or the time during class,” Sahaana Mehta, junior, said. “It doesn’t make sense to take a child’s phone away because they were checking the time. That’s honestly just a little over the top.” Mehta also noted that listening to music helps her concentrate when working independently.

“I understand that [the policy] is for the benefit of our learning and our focus [but] it’s like having our phone usage dictated, and nobody likes being told what to do,” Sofia Rodriguez, sophomore, said. While Rodriguez “knows better than to be on her phone in class,” she feels that her “autonomy [is] being limited” with the phone ban.

While opinions about the classroom phone ban vary amongst students and staff, one thing is certain, according to Matyuch: “I am sure that when these seniors reconnect at their ten-year reunion, nobody will say, ‘I wish I spent more time on my cellphone when I was in high school.”