On Halloween, many BOHS students sit at their desks waiting for the final bell to ring, eager to begin trick-or-treating or attend a spooky party. But for many others, especially those of Mexican descent, Oct. 31 marks the beginning of another celebration: Día de los Muertos.

Dia de los Muertos, also known as Day of the Dead, is a Mexican holiday where families welcome back the souls of deceased loved ones to nurture strong and lasting relationships. The holiday is traditionally celebrated from Nov. 1 to 2, but for some families, the festivities begin as early as Oct. 31.

For 24 hours beginning the eve of Oct. 31, the spirits of children rejoin their families, and the following day, the spirits of the adults arrive for a once-a-year opportunity to reconnect with living loved ones.

Nov. 1 is Día de Todos los Santos, also known as All Saint’s Day, a time for people to honor deceased children and those who led pure and innocent lives. Most celebrants use this day to visit cemeteries to praise their departed relatives. Their families gather to feast, drink, dance, and play music with their loved ones.

“We spend [Día de Todos los Santos] setting up the ofrenda and making sure everything’s good,” Brooke Leon (‘28) said. “On the second day it’s more of a family gathering.”

When Leon’s family celebrates in Mexico, they visit their loved ones’ graves and converse about cherished memories while other community members dance around the cemetery.

Then comes Día de Todas las Almas, All Souls Day, on Nov. 2, when families visit cemeteries to pray, tend to their loved ones’ plots, and leave offerings.

“On the days of celebration, we go to the graveyard and we set up a small camp,” Isabel Jimenez (‘28) said. “We sit down around [camp], and try to communicate with our family, telling them how we’re doing and how our lives have been.”

Dia de los Muertos celebrations vary across America. For those like Jimenez, who have relatives in Mexico, but live in the United States, celebrating in both places offers a chance to experience the traditions with subtle contrasts.

In California, Jimenez describes the cemetery visits as “kind of separated” for each family, but in Mexico, “everybody’s comforting” and celebrating together.

A tradition common to both Mexico and U.S. families are ofrendas, altars of offerings that are decorated with different “levels.” Two-level ofrendas represent earth and heaven; three-level ofrendas include the purgatory; and seven-level ofrendas signify the steps to rest peacefully.

Daisy Arias, Spanish teacher, sets up an ofrenda in her home with each of its six levels dedicated to meaningful people in her life. At the top of Arias’s ofrenda are her mother and grandparents, and just below are levels for her godparents, uncles and aunts, family and friends, and pets.

Arias also adds La Calavera Catrina, “The Dapper Skull,” a lady-figure who represents the cycle of life and death, on her tía’s (aunt’s), godmother’s, and mother’s section of the ofrenda.

“I lost my tía in 2006, so I got her [a La Calavera Catrina] on the way back from her funeral in Mexico,” Arias said. “Then in 2017, my godmother passed away so I got her a blue one. Then the following year, my mom passed away, so I got her a red one.”

“Even though it’s meant to represent death, [La Calavera Catrina] is still joyous, lovely, and full of life,” Arias said.

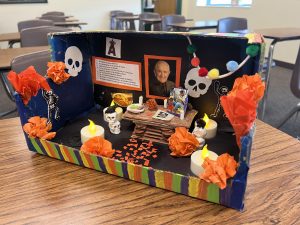

This year, to celebrate Dia de los Muertos, Spanish teacher Omar Barceñas assigned an ofrenda project to his students. Students used shoe boxes to craft miniature ofrendas honoring their own deceased family members.

Items in the student ofrendas represent each of the four elements. Earth is displayed by pan de los muertos (bread of the dead); wind is portrayed by papel picado (paper banners) that wave in the air; fire is represented by the flame of the candles; and water is portrayed by a glass of water.

“For our family, the [number of levels] is generational. On the top is my grandpa and on the bottom are more recent deaths,” Leon said. Leon’s ofrenda included her grandpa’s favorite drink, CD, cartoon character and marigold flowers.

Other students decorated their ofrendas with skeletons, paper banners, loved one’s favorite items, battery-operated candles, photographs, and different types of flowers, like marigolds.

Marigolds are another significant symbol of Día de los Muertos. Celebrants scatter the flowers, which are said to represent the sun and act as a guide for the souls to return home, to create a path from the front door of the home to the ofrenda.

There are two other flowers significant to Día de los Muertos — white baby’s breath, which represents purity, and bright red velvet flowers, which add a splash of color to the ofrendas.

The Día de los Muertos grand parade is held in Mexico City on Nov. 2. The parade – comprising performers and dancers in lively makeup and costumes – travels from Puerta de Leones in Chapultepec Park, to Avenida Hidalgo, to Zocalo.

In the United States, cities with large Mexican populations, such as Los Angeles, Chicago, and San Antonio, also conduct city-wide celebrations, including parades and street fairs.

No matter the scale of the celebration, Dia de los Muertos is, for all celebrants, a cheerful occasion of remembrance and a time for living relatives to honor the souls of their dead.

To Jimenez and many other BOHS families of Mexican heritage, Dia de los Muertos “means love.”