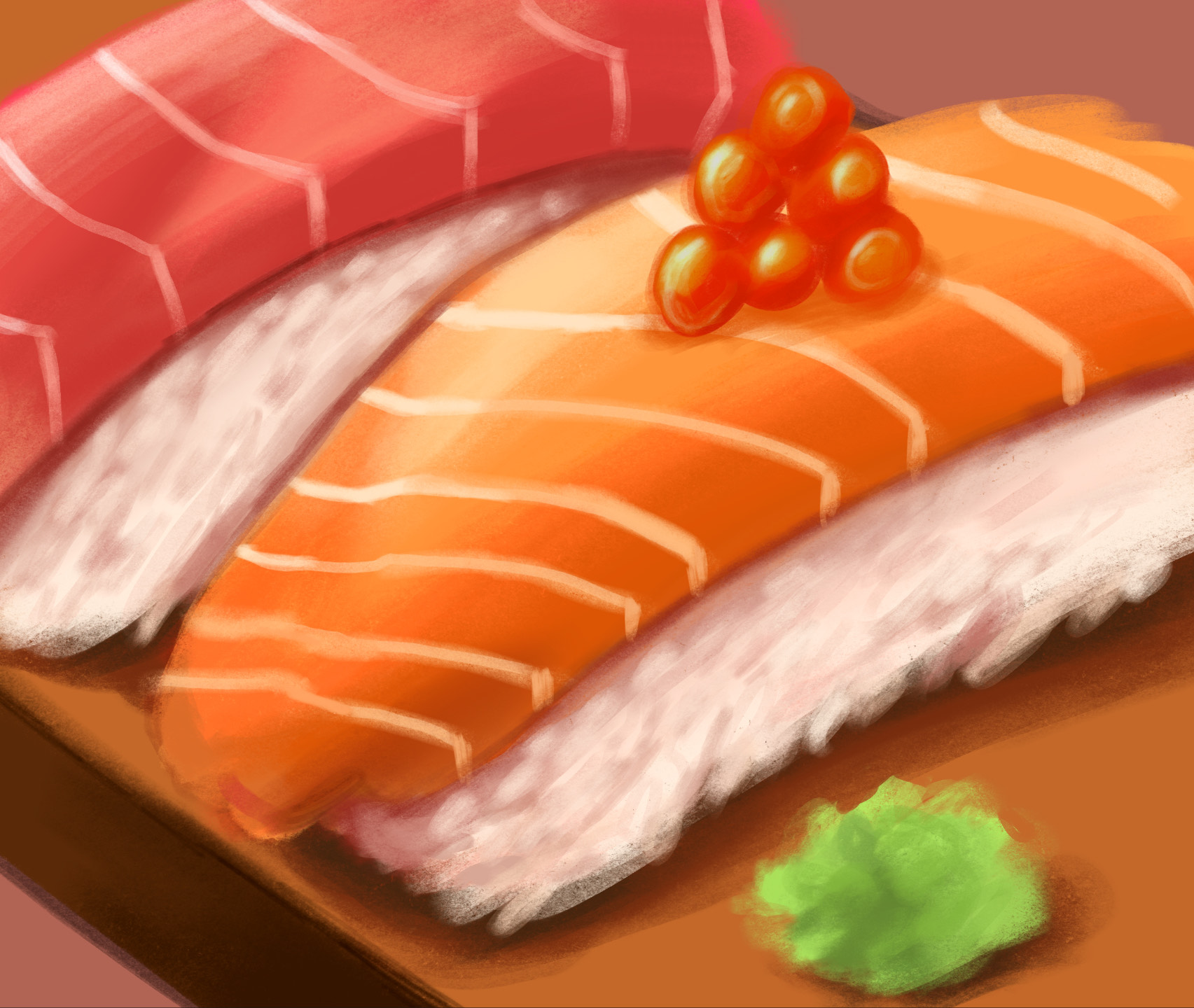

Slices of colorful sashimi — ruby-hued tuna, tangy orange salmon, pale pink yellowtail, chewy white octopus — lay in perfect rows on a plastic-wrapped, lettuce-lined plate. I watch impatiently as my mother peels back the plastic wrap and piles the glistening slabs onto our plates. My jiichan’s (“grandfather” in Japanese) sashimi arrangements are always beautiful, and I know from years of experience that they taste even better.

Sashimi plates, at this time in my life, were a beloved family tradition.

Jiichan had made a career out of fish peddling, selling the raw, ice-packed goods out of the back of his truck to the many regular clients he accumulated over the years. Even after retirement, he still continued to procure good fish for his family.

He was a master at preparing sashimi — his slices the perfect thickness, striking a balance between paper-thin and chewy. The fish he bought was always extremely high quality — rich, tangy, and flavorful. I’ve eaten often at Japanese restaurants and have sampled their sashimi, but I have never tasted any as good as jiichan’s. I’m not sure I ever will.

Jiichan’s sashimi plates were more than just a family dinner, though. They were his way of showing the love he had for his family. Because he was never particularly good at communication, or spending time with others. (I don’t think I had a single conversation with him that lasted more than a few sentences.)

Jiichan’s English was rough, thickly-accented and often intermingled with Japanese. (My own understanding of Japanese was frustratingly nonexistent.) He had a unique way of enunciating, his words loud and heavy on the ears. I struggled to understand him most of the time. Whenever we saw each other (only on holidays, or the occasional visit to my grandparent’s house), he would shout my middle name, “Sayuri!” (never my American first name, Caroline), and maybe make a comment (“You’re so old now, huh?” or, “You should learn to drive and take me bowling”). He would laugh then, and his eyes, whose lids sagged so much they looked closed most of the time, would crinkle up even further in the folds of his sun-browned face. I would yell back an answer as best I could, as he was hard of hearing (another difficulty for our communication) and that would be that. Our conversations were as short as they were rare.

Thus, Jiichan communicated through food.

He was never a very affectionate person, at least not in the obvious ways. His cooking spoke volumes, however. Sure, he barely ever talked to his granddaughters, or even his eldest daughter, my mom. Sure, we sometimes didn’t even get to say “hello” to him on the days he visited our home to drop off sashimi because his beat-up old van was easing down the road before we even knew he had come. But what other grandfather would spend hours putting together an entire plate of meticulously prepared (and very expensive) fish for his family?

My sisters and I scarcely spoke a few words at a time to our jiichan, but we knew he loved us a lot.

But did we love him, too?

I can’t speak for my sisters, but I know that my own feelings about Jiichan were, for lack of a better word, complicated. When I was younger, I liked him because his visits often meant sashimi for dinner, without any of the dreaded social interactions that adults usually expected. As I grew up, my perspective of him began to be shaped as much by the stories I heard about him from my mom and aunts as it was by my own experiences.

There were good memories surrounding him: how, when she was a child, he let my youngest aunt get away with pretending to fall asleep on the couch after he came home from work so that he would carry her to bed. There was also the time, some years later, when he mortified the entire family by trying to order a McDonald’s meal at a completely different restaurant, and then proceeded to get angry when the waiter informed him that their establishment did not serve Big Macs. Jiichan, understand, was the kind of person who did whatever he wanted, without any shame or regard for the consequences. He was the kind of person who worked hard, for both himself and his family. He was rude and generous, infuriatingly stubborn, and tremendously hardworking.

He was a lot of things, both admirable, and not.

In the years leading up to his death, I found myself forgetting to see his better qualities. It was during this time that he suffered his first stroke, a process made all the more difficult by his refusal to comply with hospital staff and recovery procedures. In his eyes, they were taking away his independence. To the rest of us, he was making an already stressful, painful situation so much worse than it had to be. I still remember, vividly, how my mother complained, how my aunts grumbled, how they all despaired about his recovery.

“He’s like a child,” my mom once said, and I found myself agreeing with her.

It was a relief to us all when Jiichan was finally allowed to come back home. There were still small struggles (he refused to use his walker, for example, and there were countless times he tried to sneak off to work in his garden), but for the most part, things began to settle down. He was even able to make sashimi again.

It was a shock to my family when, less than two years later, he abruptly passed away from another stroke while sleeping at home.

In the wake of his death, I’ve found myself wondering if I did really love him. I know that I resented him for the pain his stubbornness caused my mother. I know that when trying to describe him to a friend a few years ago, the words that left my mouth were, “He’s interesting. Not in a good way.” I know that I wished many times for him to be more sensible, more agreeable.

But I also remember the countless sashimi plates, the lovingly cut slices on each platter arranged with great care.

I know what those plates meant to me, and what they meant to him.

I know that I miss those plates terribly.

But did I love my jiichan?

It’s not as easy as a “yes” or “no” question. But I will say this: When I try to remember Jiichan, the first thing that comes to mind is not the awkward, half-understood conversations, or the McDonald’s story, or the frustration on my mom’s face every day that he had a new “incident” at the hospital. Instead, it’s a plate of sashimi, still fresh, made for the people who mattered to him the most, the people he loved.

John-Michael Patino • Jan 7, 2025 at 1:15 am

Thanks for sharing your story! Perhaps you can participate with the Japanese Culture Club and document when the Hanno students visit BOHS week!

Jacquelyn Nethers • Dec 11, 2024 at 7:59 pm

Beautiful storytelling.