“And do you eat the seed?” my teacher asked.

It was a silly question. She was two, maybe three, perhaps four or five times older than I (I was not really sure as I had very little concept of age).

I looked at her, puzzled, but nodded to confirm that yes, you do eat the seed. It was a funny sight, somebody who often taught me complex things, like how to count to ten, or to sing songs about the days of the week, being taught to eat something as simple as a pomegranate.

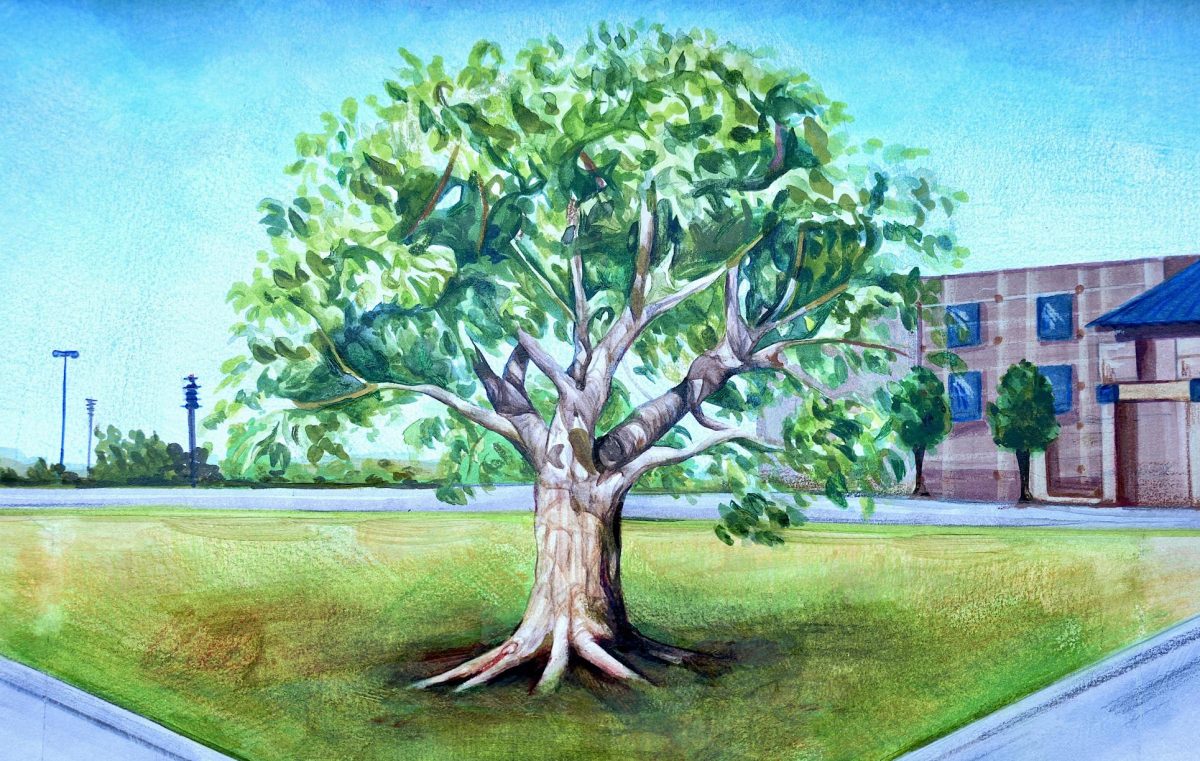

These pomegranates had been picked from my bà ngoại’s (“grandmother” in Vietnamese), well-kept garden. She planted it when she first moved into her home, which she carefully selected to be a short drive from her sister’s house; a shorter drive to the nearest Vietnamese market; and an even shorter walk to her best friend’s house (whom she had met in girl’s school back in the old country).

The seed she had planted had since grown from a sapling into a beautiful tree with broad, winding branches sprinkled with bright green leaves and the bright red orb of the pomegranate fruit.

But pomegranates were not the only fruit that Bà Ngoại labored over for so long. She risked her life when fleeing her home, Vietnam, so that my mother, and then me, would have better lives, brighter futures.

Bà Ngoại traded all of her belongings for gold to secure passage on overcrowded, undersized boats. The boat was unbearable, Quyên, she said to me once, before I lost my fluency in Vietnamese (broken now, with accented English to fill in the gaps between my sad attempts at Vietnamese). Bà Ngoại explained that the boat had awfully low rations of food, but she would often give whatever she could wrangle to my mom and uncle. She felt suffocated, she said, not only by the briny smell of the sea, but by the heavy fear that lingered over the boat people.

The flimsy boat was an easy target for pirates, and an even easier target for the ocean which never stopped threatening to tip the vessel over.

Bà Ngoại arrived in America eventually, but the trials continued. She traveled by Greyhound bus from Florida to Garden Grove, Calif. where she began to rebuild her life. She settled a short distance from Little Saigon and found a job with the United States Postal Service, working night shifts and long hours to afford a better life. Bà Ngoại was often exhausted and yearned for the comforts of her past, of her homeland, of her family. There was one place in particular, however, where she could always find solace: her garden.

Her backyard was her sanctuary. Kept tidy and meticulously maintained, Bà Ngoại fostered her plants with love. She planted many trees, among them the tropical fruits that reminded her of the country she loved so much.

She retired, eventually, settled into this no-longer-so-foreign country, and continued to maintain her garden. She gifted her neighbors baskets of fruit from her garden, her way of showing love.

These are nowhere near as good as they would be if we were in our motherland, Bà Ngoại said to me as she handed me a plate of assorted fruits. “Our motherland?“ Vietnam was her motherland, not ours. I was born in Fountain Valley, not Saigon.

My resistance to her “our” was due to an inner dialogue I had developed over the years (I was seven then), a voice that told me that my Asian heritage was my worst feature, that it was something to be ashamed of.

I pondered the idea of Bà Ngoại’s motherland being mine as well (not possible, I decided) as I grabbed handfuls of fruit from the plate she had given me.

By then, I had stopped speaking Vietnamese almost entirely, but a accent remained, stubbornly. I wanted so badly to fit in at school so I focused with utmost concentration on enunciating my t’s, something my peers said sounded “funny.”

I grew up like this, trying my best to speak “normal,” to be normal. I hid the exotic fruits that my grandma packed in my backpack, the fruits that she had carefully hand-picked and then placed into pink plastic bento containers that she had bought on clearance at the local Vietnamese market. I hid my fruit like I had hid my language. But mostly, I was hiding a part of myself — the part that is why I am here today, privileged and lucky.

Now, as a 14-year old, I look back at those moments of undeserved shame with embarrassment. I am embarrassed for the little girl that felt pulled between two cultures. I am embarrassed for the little girl that purposely lost the language that she once spoke with such fluency. I am embarrassed for the girl that felt embarrassed.

Bà Ngoại still picks pomegranate for me, and there is nothing better in the whole world than the taste of the bright red, seed-filled fruit. It tastes like love and labor, and of Bà Ngoại’s lifetime of bravery.

Without fail, I go to her house in Garden Grove each Wednesday, and speak my far-from-perfect Vietnamese, attempting to make up for all the years I only spoke English.

And every Wednesday, without fail, Bà Ngoại sends me home with a few Ziploc bags stuffed full of bright red pomegranates, the fruits of her labor and love.

Jan Anderson • Jan 17, 2025 at 7:00 pm

So descriptive! Thanks for sharing this part of your heritage.