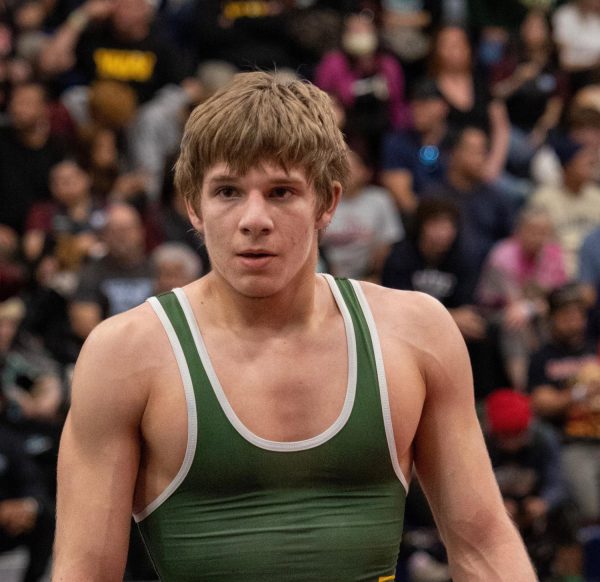

Nakayama Stays True

Japanese sport of kendo connects senior Noah Nakayama to his Japanese roots

At the ready of the judge’s signals, Noah Nakayama, senior, raises the bamboo shinai, pacing back and forth to dodge his opponent’s swings. After a swift trade of parries, Nakayama lands a successful jab at his opponent’s stomach, and the tokei gakari (timekeeper) raises a flag to signal the end of the round. Walking to the center with his opponent, they respectfully bow to each other and step backwards, marking the end of the match, and another kendo win for Nakayama.

Nakayama’s journey with the ancient Japanese sport of kendo began when he was eight years old when his mother introduced him to the family’s kendo tradition, a tradition that has been passed down through generations on the maternal side of his family. Ever since, kendo has been a way for Nakayama to reconnect with his mother’s side of the family and to bond over ancient Japanese culture.

“Kendo is not just a sport, but a way of life and a vehicle for building of character with the unity of both the body and mind,” Nakayama said. “I think the cultural and spiritual aspects of kendo are super cool, and they are definitely what separates kendo from being just a sport and being a martial art.”

Kendo is practiced utilizing traditional Japanese protective armor and requires a bamboo shinai, or sword, which is used for training and competing. A full set of kendo armor, or bogu, is made up of a caged helmet called the men; a pair of padded, cumbersome gloves called the kote; and an armored front core protector called a do. When combined, the finished armor set resembles the intricate armor used by ancient samurai or traditional Bushido warriors.

Nakayama took an instant liking to his family’s tradition, training every week at a dojo (training gym) in the City of Industry with sensei (coaches) twice a week. The sensei prepare him for his physically taxing competitions. To further hone his skills, he occasionally visits other dojos around Orange County (there are about 50 dojos in Southern California), often practicing into the night until he nearly drops from exhaustion.

Nakayama competes in about seven to eight kendo matches a year, with each one separated into different rankings or age groups. Each match pits two kendo players against each other, which is judged by three judges, or referees. Competitors must obtain two points in total to win the match by striking the head, stomach, or wrists, or have more points than the other player by the time runs out.

Nakayama’s long-term training and dedication to kendo has led to winning individual third place at the 2016 Junior National Championships in Detroit; ranking as the third best kendo player in his age group in America (according to Nakayama); and winning first place in the National Championship with his SCKF regional team at the 2017 National Championships in San Jose.

Kendo originated about 1000 years before the Edo Period (1603- 1867) ended, where samurai warriors “worked for their lords, protecting and fighting for them using weapons such as swords, spears, bows and arrows,” according to web-japan.org. By the 17th century, however, Japan was at peace, and the battle-trained samurai were no longer required to serve. This freedom gave way to kendo, in which these former warriors used bamboo swords as a medium to strengthen the mind and the body through training.

This focus upon unifying the strengths of the mind and body is something that both the samurai of the 17th century, and Nakayama, draw inspiration from, connecting centuries of tradition in the process.

Masako White, Japanese teacher, compares kendo to the struggles within our own everyday lives. “Our daily lives are very scattered [where] we have to do either this or that. [However], once [you] go into kendo, you have to center yourself. The art of using the shinai to look and see what you have to do,” White said.

Despite his success with kendo, Nakayama admits that there is a struggle to balance his time spent practicing with other aspects of his life. He stated that there are “long nights” where he has to pick up his studies after grueling hours of practice, a process that inevitably takes a toll. But instead of becoming discouraged, his “drive to better [himself] in school and kendo doesn’t stop [him] from trying less in one or the other.”

Currently, Nakayama has his eyes set on the American National Kendo Team, with an end goal of competing in — and winning — the World Kendo Championships, the final step in the long kendo journey Nakayama has worked so hard on.

Nakayama’s family tradition of kendo gives him a sport that doubles as a way of life. His respect for the spiritual importance of kendo is unparalleled, and this is apparent in his individual success. “[Kendo] is basically my life,” he said. “It [has] shaped me into who I am today, and has taught me numerous life lessons. It has helped create lasting memories that I can look back on and cherish forever.”

Your donation supports the student journalists at Brea Olinda High School! The contribution will help us purchase equipment, upgrade technology, and cover our annual website hosting costs.