N-Word No More: Racial Epithet Should Not Be Read Aloud in English Classrooms

Wildcat Staff Writer Gaby Smith argues that the offensive racial epithet should be muted during in-class readings of literature.

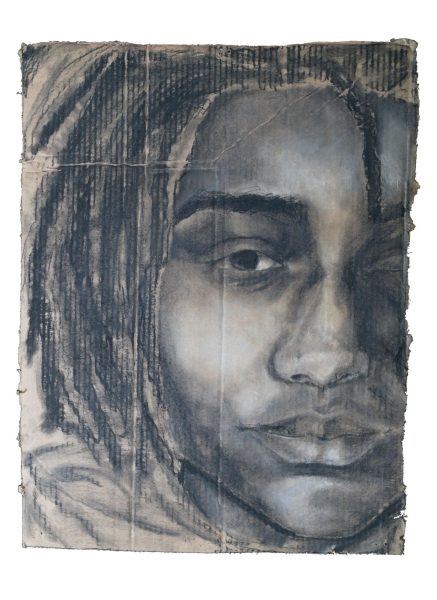

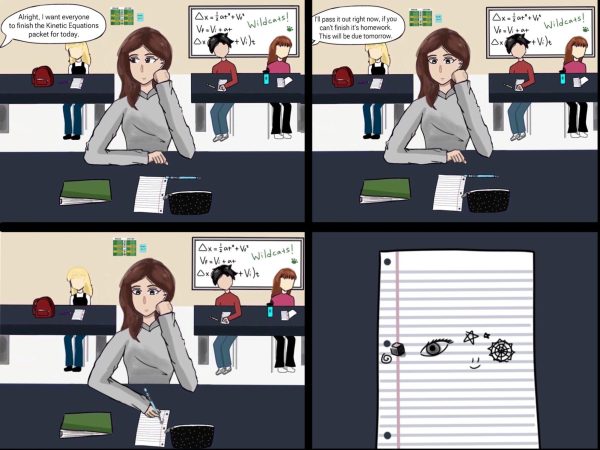

While reading Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird aloud in my ninth grade Honors Literature and Composition class, students who were captivated by the riveting stories of the Finch family, the mysterious Boo Radley, and the trial of Tom Robinson, suddenly went silent.

Atticus Finch, a lawyer, is called a “nigger-lover” by Cecil Jacobs for defending the Black field hand, Tom Robinson. When the racial epithet was read by my teacher (who read passages of the lengthy novel aloud to break the monotony of silent reading), the atmosphere in the room grew noticeably uncomfortable and students looked to their peers, uncertain how to react after hearing the most taboo word in the English language.

It was at that moment when I questioned if racial epithets—even when used in literature—should be read out loud in classrooms.

Bluntly, the word should not be read aloud in class—even when reading from assigned literature—as it dehumanizes Black people and reinforces negative stereotypes. But simply skipping over the word while reading aloud in class is not enough—there should also be more education in BOHS’s English classes about the impact of this slur, both in literature and in society.

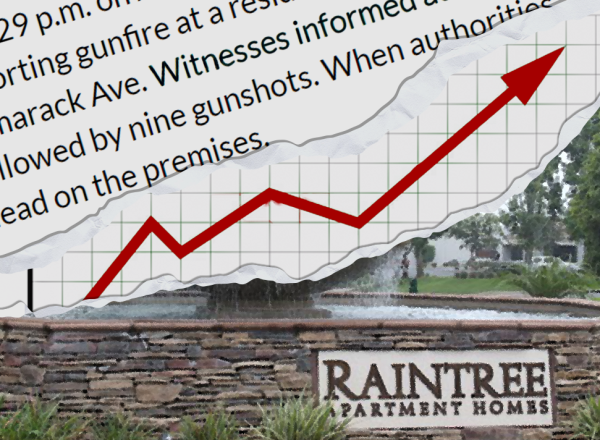

In just the freshman and sophomore years of English classes at BOHS, students will encounter the slur 65 times, once in William Golding’s 1954 novel Lord of the Flies; 16 times in John Steinbeck’s 1937 novella Of Mice and Men; and 48 times in Lee’s 1960 novel.

epithet: a disparaging or abusive word or phrase

But despite the word’s prevalence in three of the English department’s core works, and despite BOHS’s increasingly diverse demographics (68.3% of our student body identifies with a race or ethnic group other than white), students will never have an open discussion, nor learn anything of value about the word’s significance, from their teachers.

“Nigger” is derived from the Spanish word “negro,” which means “black.” This word gradually became omnipresent in American society during the period of Black American slavery and the era of Jim Crow Laws. The “nuclear bomb of racial epithets” stems from a deep-seated bigotry that has plagued (and still plagues) America, and is still used today in a colloquial manner in hip-hop, social media, TV, films, and literature.

There is harm in encountering the term. The epithet can be triggering for many Black people, and can increase stress levels, lower self-esteem, lead to embarrassment, cause racial trauma, and potentially even provoke a violent response. Further, in a 2018 study conducted by the International Journal of Society, Culture, and Language, 56% of survey participants (88% of whom are Black) believed that the n-word was completely unacceptable for anyone to use in any social setting, 76% “agreed that it is never acceptable for non-Blacks to use the N-word with anyone in any situation.”

In my English classes, racial slurs in the texts we read are never addressed in lectures or discussion. Instead, my teachers seem to treat the offensive term as archaic and no longer relevant. But there needs to be more education and discussion in classrooms about the slurs we encounter. For example, instead of hurrying uncomfortably past problematic passages, a discussion should happen about why the n-word is so damaging to characters like Of Mice and Men’s Crooks, who is described as a “nigger [with] a crooked back,” and so problematic to students of color.

Shulin Raja, junior, and avid reader of American literature, concurs. “I don’t think that slurs should be relegated and locked into some aura of mystery that leads people to not have a full understanding of what they mean and how certain slurs came to be,” Raja said. “Teaching children when they’re young the origins of certain words and what they can mean to people is something that we can benefit from. It creates people who are more aware of how what they say can affect others.”

While some might argue that preserving the integrity of a work of literature is essential, repeating slurs that were said by characters—like Bob Ewell describing Tom Robinson as a “black nigger”—do not take away the brilliance of the stories. Skipping over slurs, rather, acknowledges the slurs’ presence and power more than actually reading the word aloud. The author’s purpose in using the word is given more weight when avoided because it shows that the word is so derogatory that it shouldn’t even be uttered in class. Muting John Steinbeck’s description of Crooks as a “busted-back nigger,” for example, allows readers to better understand how vile the word is if it doesn’t even have a place in the classroom.

Kaylee Neidiger, junior, agrees and believes that To Kill a Mockingbird and Harper Lee’s storytelling is not marred if students do not read the numerous slurs aloud.

“The severity of the word creates an impact in the writing, and it’s okay to acknowledge why it’s present in the text, but out of respect for the word’s tragic history it’s best to ignore the word. The entirety of Tom Robinson’s case was based around a White woman who falsely accused him of rape. You can easily understand [Lee’s] point and the severity of the situation without [saying] the full n-word,” Neidiger said.

racial slur: a derogatory or insulting term applied to a particular group of people

Although these slurs should not be read aloud, books that contain these slurs should still be read in schools. These important books tackle themes like racism and prejudice and offer windows into different eras—To Kill a Mockingbird is set in racism-plagued Alabama in the 1930s; Of Mice and Men is set in California in the 1930s; and Lord of the Flies is set on a tropical island during war-plagued 1950s.

In order to understand why Tom Robinson’s trial is unjust; why Crooks is being tormented by the Soledad Ranch field hands; and why Piggy would ask, “‘Which is betters—to be a pack of painted niggers like you are, or to be sensible like Ralph is?'” in Lord of the Flies, we have to read these sometimes unsettling stories, but we also must discuss them.

With more books being taken out of school curriculums for having language deemed “insensitive”—like To Kill a Mockingbird being banned in the Burbank Unified School District—the way we approach mature literature will be in discussion. These books challenge people’s morals and start different—and sometimes eye-opening—discussions.

Verronica Clements, English teacher, considers books that contain racial epithets significant as they act as a window into the past that also reveal a lot about the present.

“We need to continue to have discussions about how far we’ve come in relation to race, and reflect on what we can do to create a better society today. I think it’s important to know how far we’ve come and what things were like, because I think to not go back and look at what what actually happened wouldn’t do [the book] justice,” Clements said.

For the next class of freshmen, students reading To Kill a Mockingbird will hopefully understand—through omitting the n-word—the harm of Tom Robinson being called a “black nigger” by Maycomb’s racist residents, while also understanding how the use of the word affects Black people today. By understanding the word’s significance—from teachers providing historical context, mostly—students will gain a perspective that my class, and others, did not get.

Gabrielle Smith, senior, will attend Howard University this fall.

Joe • Nov 16, 2023 at 6:28 am

“noticeably uncomfortable and students looked to their peers, uncertain how to react after hearing the most taboo word in the English language”. This is the whole point of the use of the word in many books, it forces the kids to think about actually hearing the word in context. The same reason the word is used in movies of today like Django or American History X. I agree with most of your sentiments, but to truly understand the negative connotation the word holds, you have to include it in the media.

Parent • Feb 24, 2023 at 9:43 pm

Yay, to this young writer! She shows more wisdom in her opinions than her instructors. And while the class seemed uncomfortable, I would be weary of the one who reads aloud without discomfort. However, reading the same text year after year after year after year, does tend to desensitize one. Perhaps next time the author should ask a professor of color for their opinion on the subject, someone who the term actually affects. I would be more interested in their opinion.

Grant • Jan 8, 2023 at 3:35 pm

The thought of banning whites in general from saying the n-word to me sounds like infringing on the right of free speech. (forgive me if I’m wrong, respectfully of course)

Kayla • Jul 26, 2022 at 10:54 am

Thank you! The way my teacher tried to justify it was by saying us students needed to feel the “impact” this word had on black people back then.

What she failed to understand was that I as a black student, already felt the impact of that word. I’d heard that word throughout my life and it always, ALWAYS, made me feel unsafe, unwanted, and outcasted.

To be honest, none of the white kids cared about how the N word made black people feel, in the past or the present. They still said it regularly and jumped down my throat when I told them to stop.

It felt like she cared more about protecting the authenticity of the book rather than protecting the only student negativly effected by that word.